150 Years: The Power of a Story, part 2

This article is part of a series that we will share throughout the 2020-2021 school year to celebrate the 150th birthday of Dr. Maria Montessori. Check back often for more posts that reflect on the past, present, and future of Montessori education.

Last month we shared the story of Montessori educator Shawnaly Tabor. This month we highlight the Montessori journey from a different perspective: that of the student. Neshima (17) and Emet (15) Vitale-Penniman are adolescents that began their Montessori primary education at a public Montessori school, and during their lower elementary years transitioned to a private Montessori school. Emet currently attends The Darrow School, where Neshima graduated from this past spring as valedictorian. In addition to their schoolwork, both children work alongside their parents Leah Penniman and Jonah Vitale-Wolff, co-founders of Soul Fire Farm. (Photo credits: Soul Fire Farm website)

Let’s start at the beginning. What are your earliest memories of attending a Montessori school? What did you take away from your time in a primary class that you look back and are glad to have experienced as a young child?

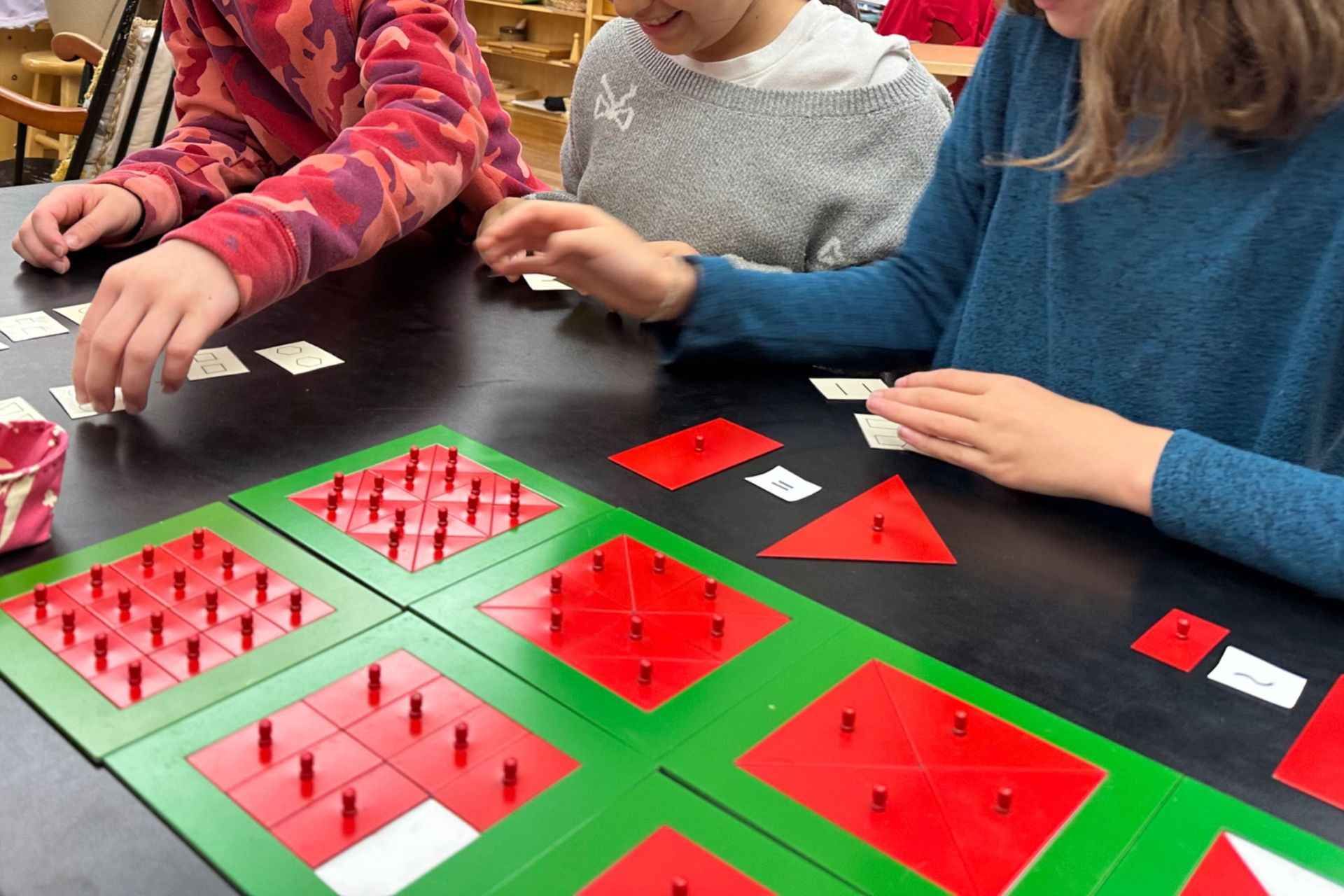

Emet : One of my first memories that I always think about looking back is making patterns with little plastic bears, and just little simple things like that. Making patterns led to complex math equations. Being able to do hands-on learning with materials such as the multiplication board was really helpful.

Neshima : Similarly, just experiencing lots of opportunities to do work that was really formidable and fostered deep-set curiosity, and having a lot of support with finding work that met me where I was at in my academic journey. Just finding things that quenched my curiosity and my love of learning and having teachers that were really supportive of that.

You first attended a public Montessori school before moving to a private Montessori school in lower elementary. Keeping in mind the differences between the two settings, what types of support do you think public Montessori schools might benefit from?

E: With public schools, there are a lot of requirements such as tests, but when I went to private school, they were able to design their own tests that were not required by the state, and I think Montessori should be able to have that freedom so you can go at your own pace. At my public Montessori school, I was working just with kids at my own grade level, but at private Montessori if I wanted to excel in math, I could work with kids at another grade level, but for other subjects still work with kids my age. That was really valuable.

N: That was something I wanted to touch on as well; removing those requirements around testing and this very linear model of academics that public schools are required to adhere to. Also, regarding discipline, at my first Montessori school sometimes small mistakes would result in taking away recess time, in a way that didn’t give students an opportunity to grow. Alternately, at the other school, I felt more invited into a process of changing behavior and acting responsibly, and just building those skills.

How do you think Montessori schools support kids academically? What happened if a subject area or skill was hard for you, or if you felt like you needed more of a challenge?

E: I love how Montessori teaches in a way that you can excel at something and be challenged, because it’s a curriculum built around you, and you’re able to do things that you feel challenged by. But if you’re struggling with something you can get extra help from teachers because there are small classes and just the general learning style. I just love it.

N: For sure, I think the differentiation of being able to move ahead, working with teachers to find work that meets you wherever you’re at or finding a material that’s more interesting or challenging, and being able to work alongside other students that were on the same path and doing the same work, no matter what grade they were in. So, it didn’t matter if you were on a slightly different journey than the standard curriculum. That was something that was really helpful, and that I tried to bring into my high school experience as much as I could with independent studies, so that I could move at my own pace.

Academics are one small part of who we are as we grow. How did your Montessori experience support your growth as a social and emotional person?

E: Montessori helped me learn how to build authentic, deep relationships with people. I still have a lot of friendships that I built in first and second grade. You’re able to learn together, play together, do so many things together, but also take space if you need it. It lets you cultivate relationships and friendships with people. It’s a good space for that.

N: Two things come up for me: One is building strong and accountable relationships with people that are my age - not being afraid to approach someone if there’s a conflict between us, not being afraid to figure out how to resolve it, because I was given some of those tools. The other is having confidence in relationships with adults, just because I felt so close and trusting of my teachers throughout Montessori. I now feel very much able to approach adults with questions I have, or asking them about their life, or for stories, or talking about politics, even. I feel so much more comfortable with that, being able to have these really authentic and meaningful connections with people that are a lot older than me - or even younger than me - just having that range of connection and experience is really meaningful for me.

Maria Montessori thought that educating children with her methods had the potential to change the world. What do you think?

E: I agree with that and it definitely does. The whole Montessori curriculum is about being able to pursue what you want and going at your own pace, building friendships and relationships, and I think that really does have the power to change the world. If everyone were to go to a Montessori school, I think the world could be a pretty great place.

N: Yes, I definitely agree with that. I think it’s so important in these times to have people that are really empathetic and that seek to fully understand another person or situation. So often we get into these really polarized mindsets and it’s easy to just adhere to one set of beliefs or values, and so it’s really important to have people that are curious about others and curious about learning things for the sake of learning not just to pass a test or to memorize, and to apply that to a worldview, and their efforts toward social justice or whatever they’re fighting for. Fully understanding a situation, fully understanding a story is so important, and it’s something that Montessori definitely instills in its students.

Also, regarding conflict resolution: having those tools to approach a challenge with another person or a group of people in a really mature and thoughtful way instead of lashing out and being violent - either with words or physical action - is a really important tool.

Are there life values that you feel are important that were supported during your time in Montessori schools?

E: Building off what Neshima said, just making sure to get everyone's opinion and sit down and talk about something. To really sit down and have a conversation that needs to be had after a conflict - that’s one of the values I think is so important and I definitely learned from Montessori.

N: A big one, at least in my life, is a love of learning and curiosity. I think that’s so strongly ingrained into Montessori students and applies to both the academic world and beyond. For myself and friends, we love to explore things for the sake of understanding them and just for the sake of that experience. Not to impress anyone or to make any money from it, we really just love to learn about new things. We have an understanding that we can take whatever our passion is and turn it into something that we can pursue for our lifetime - whether that be a career or not. For me that’s been really meaningful, it’s been something that’s carried me through my high school experience and now into gap year and college experiences; it has very strongly guided my path and the way I navigate my life now - that curiosity, that passion for learning.

How has your Montessori education affected who you are as a person today? What are you up to now and what are your plans for the future?

E: Montessori shaped most of who I am. It built values of being kind to people. I probably wouldn’t be at Darrow if it weren’t for Montessori, because I liked how similar they were, with close relationships to teachers, small class size. Those are things I really enjoyed in my Montessori schools; I wanted to have good relationships with my teachers and small class sizes.

Now I am working at Soul Fire Farm creating video series. I’m editing a video series right now for the farm, as well as helping my mom farm and helping my dad with carpentry.

N: Montessori very much respects students and recognizes their maturity and their ability to learn things and apply their knowledge to the world. I feel like primary students aren’t treated like little toddlers; they are treated like the full human beings that they are. This has helped me approach a lot of what I do with confidence in my skills. As a young person I’m able to work on the farm and do farming and carpentry and graphic design and cooking, and feel really dignified in my work even though I’m a young person. I feel like I deserve the pay and praise I get; I feel like I deserve the support I get. I have the sense that the things I do are valued, even though I’m a young person and haven’t gone to school to study about it.

I just graduated high school, and even though it’s very unsettling times I had already been planning to take a gap year. I graduated one year early with the intention of using that fourth year to do a lot of hands-on pursuits of things I’m curious about. I don’t know what I want to pursue career-wise. I don’t think I would have the courage or foresight to do this without Montessori. I was accepted to Brown University, so I will be attending there after my gap year. One of the main reasons I chose that school is because similarly, they allow so much space in the curriculum for curiosity and exploring the things you’re passionate about, and finding the ways they overlap. Working with other students and schools to figure out interdisciplinary solutions to global issues and engineering challenges; that felt like something that was so magnetic and important to me in my college experience.

Is there anything else you think people should know about Montessori education?

N: I love the concept of working toward making Montessori accessible for more people. It’s so important to have low income and POC communities have access to this kind of education, because it is so formidable and so transformative for a lot of people.

I think about how much my parents have been involved, and how much Montessori students are able to invite their parents into their learning...even recently having online school during my last months of high school: I would have design challenges and could ask my dad or brother to work with me. That Montessori mindset is to think of learning as not just independent, it’s something I get to invite other people into. I suppose that’s something Montessori parents can keep in mind; they are lucky and privileged to be excited to be part of their children’s learning experience.

Warm regards,

Candice Lin, Director

info@jordanmontessori.com